When I read a book I have the habit of highlighting certain passages I find interesting or useful. After I finish the book I’ll type up those passages and put them into a note on my phone. I’ll keep them to comb through every so often so that I remember what that certain book was about. That’s what these are. So if I ever end up lending you a book, these are the sections that I’ve highlighted in that book. Enjoy!

After transcribing a couple snippets I noticed that comics use this “bolded italicized” font style quite often to emphasize certain words or phrases (Never thought twice about it before!). I decided to keep that styling in this post to see how well it reads in a different medium.

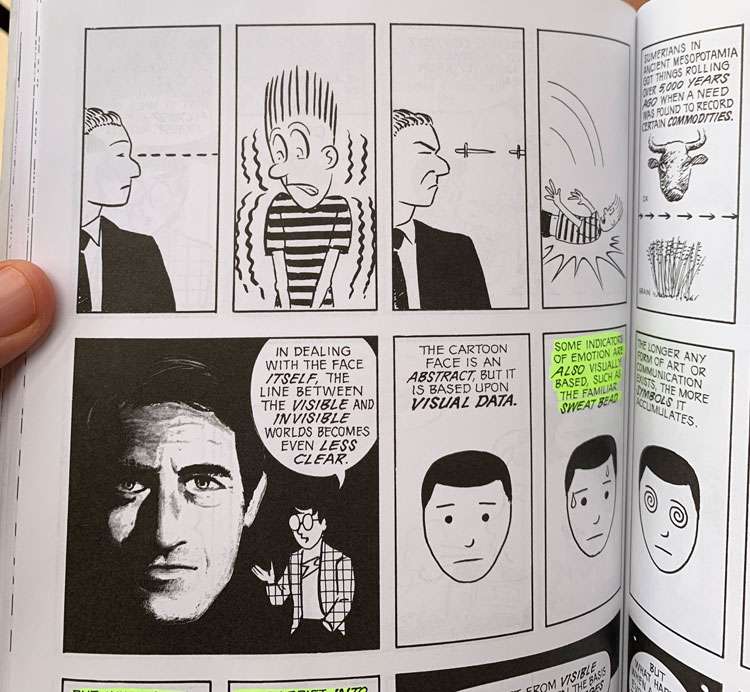

Cartoon imagery has a certain universality to it. The more cartoony a face is, for instance, the more people it could be said to describe.

We humans are a self-centerd race. We see ourselves in everything. We assign identities and emotions where none exist. And we make the world over in our image.

Thus, when you look at a phot or realisitic drawing of a face, you see it as the face of another. But when you eneter the world of the cartoon, you see yourself. I believe this is the primary cause of our childhood fascination with cartoons, though other factors such as universal identification, simplicity, and the childlike features of many cartoon characters also play a part. The cartoon is a vacuum into which our identities and awareness are pulled. An empty shell that we inhabit which enables us to tracel in another realm. We don’t just observe the cartoon, we become it!

When cartoons are used throughout a story, the world of that story may seem to pulse with life. Inanimate objects may seem to possess seperate identities so that if one jumped up and started singing it wouldn’t feel out of place. But in emphasizing the concepts of objects over their physical appearance, much has to be omitted.

Storytellers in all media know that a sure indicator of audience involvement is the degree to which the audience identifies with a story’s characters. And since viewer-identification is a specialty of cartooning, cartoons have historically held an advantage in breaking into world popular culture.

See the space between the panels? That’s what comics aficionados have named “The Gutter”! And despite its unceremonious title, the gutter plays host to much of the majic and mystery that are at the very heart of comics! Here in the limbo of the gutter, human imigination takes tow seperate images and transforms them into a single idea.

No matter how dissaimilar one image may be to another, there is a kind of alchemy at work in the space between the panels which can help us find meaning or resonance in even the most jarring of combinations. Such transitions may not make “sense” in any traditional way, but still a relationship of some sort will inevitably develop.

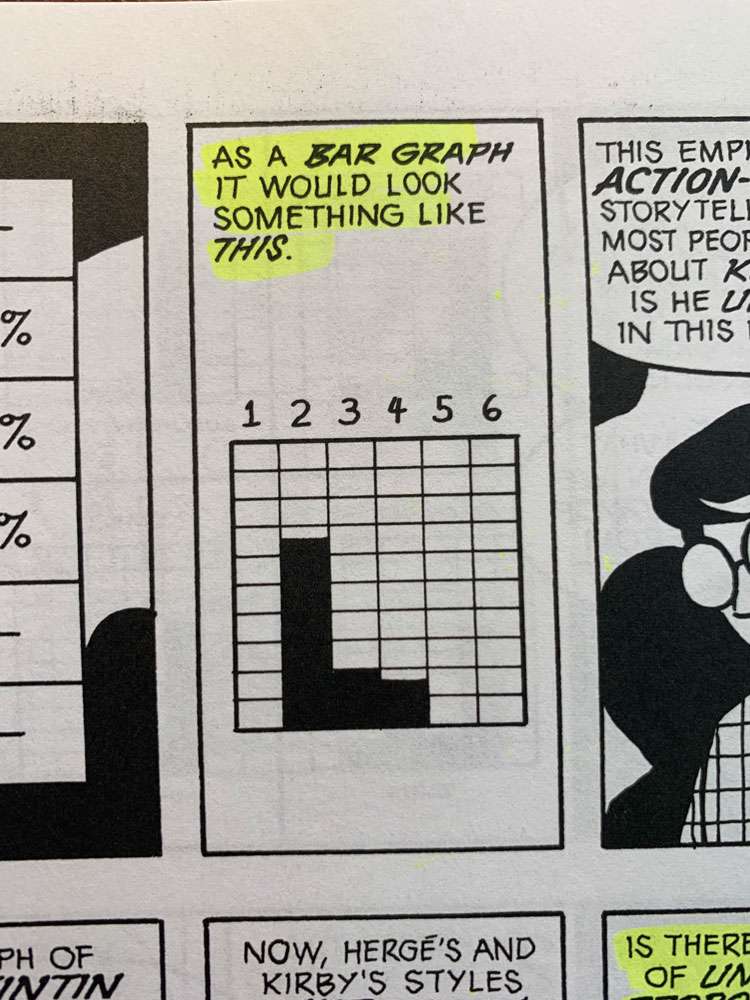

Types of transitions

- Moment to Moment

- Action to Action

- Subject to Subject

- Scene to Scene

- Aspect to Aspect

- Non-Sequitur

Most mainstream comics in america employ storytelling techniques first introduced by Jack Kirby.

The idea that elements omitted from a worls of art are as much a part of that work as those included has been a speciality of the East for centuries. In music too, while the westerns calssical traditions was emphasizing the continuous, connected worlds of melody and harmony, eastern classical music was equally concerned with the role of silence!

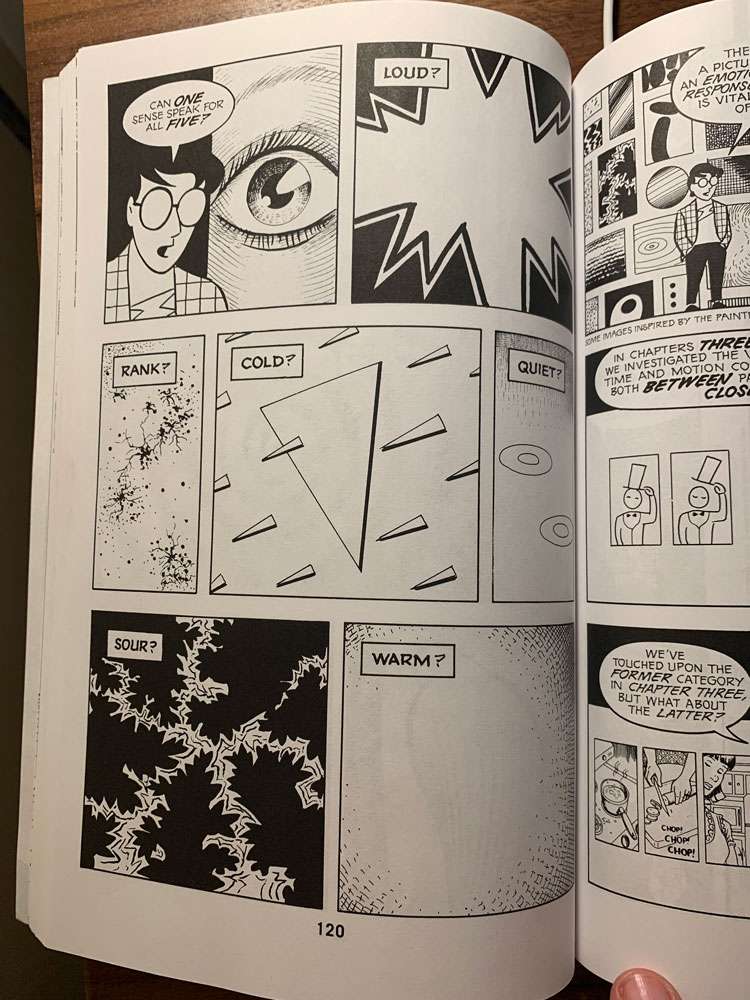

Comica are a mono-sensory medium. They rely on one of the senses to convey a world of experience We represent sound through devices such as word balloons. But all in all, it is an exculsively visual representation. Within these panels, we can only convery information visually. But between panels, none of our senses are required at all. Which is why all of our sense are engaged!

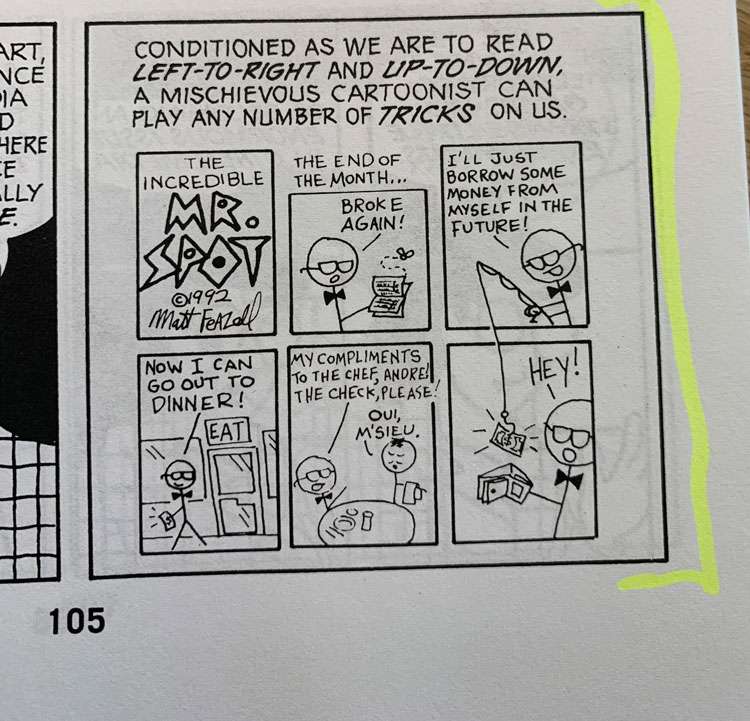

Making the reader work a little may be just what the artist is trying to do. Once again, it;s all a metter of personal taste.

No other artform gives so much to its audience while asking so much from them as well. This is why I think it’s a mistake to see comics as a mere hybrid of the graphic arts and prose fiction. What happens betwen these panels is a kind of magic only comics can create.

When the content of a silent panel offers no clues as to its duration, it can also produce a sense of timelessness. Because of its unresolved nature, such a panel may linger in the reader’s mind. And its presence may be felt in the panels which follow it. When “bleeds” are used–i.e., when a panel runs off the edge of the page–this effect is compounded.

Wherever your eyes are focused, that’s the Now. But at the same time your eyes take in the surrounding landscape of past and future!

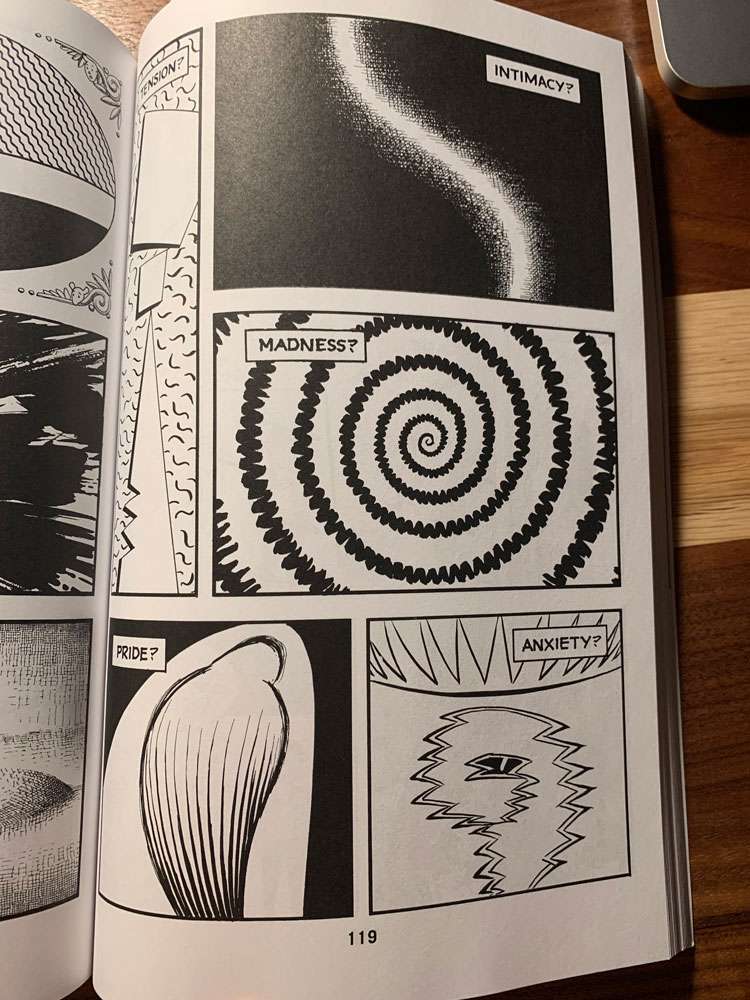

If you’re going to paint a world filled with motion then be prepared to paint motion!

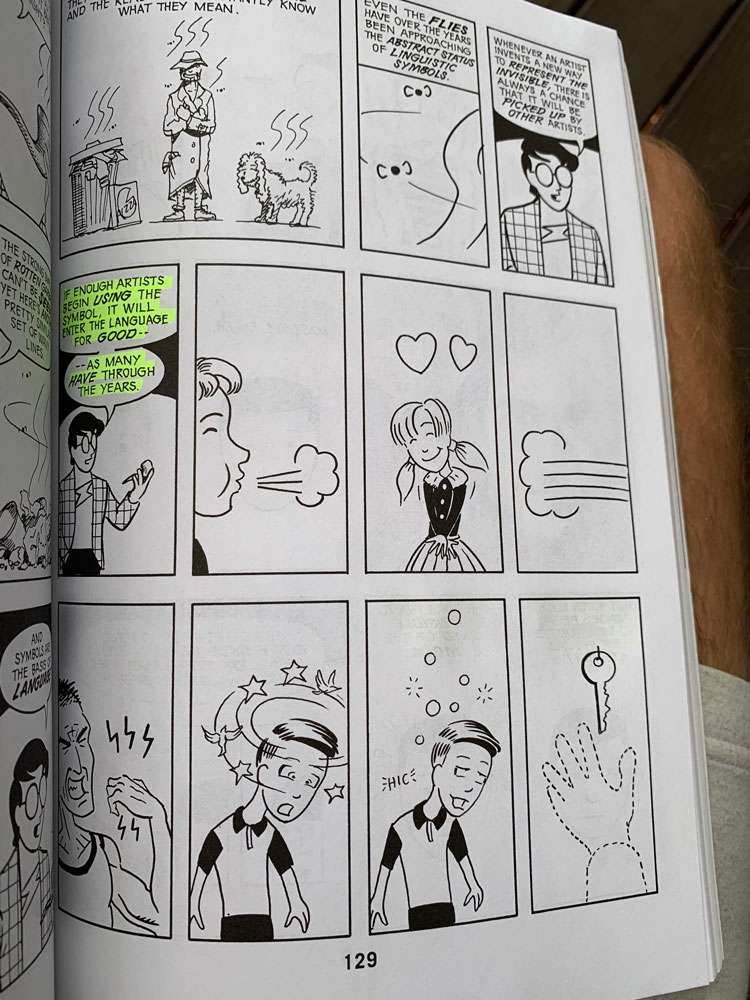

If enough artists begun using a symbol, it will enter the language for good, as many have through the years.

Some indicators of emotion are also visually based, such as the familiar sweat bead. But when such images begin to drift out of their visual context, they drift into the invisible world of the symbol.

The longer any form of art or communication exists, the more symbols it accumulates. the modern comic is a young language but it already has an impressive arrary of recognizable symbols.

By the early 1800s, western are and writing ha drifted about as far apart as was possible. (Only to slowly creep back together as we get closer to the present day. Especially with comics becoming popular.)

Pages 170-178 offer a great metaphor and accompying story to show the mastering of one’s craft.

These colors–roughly, red, blue, and green when projected together on a screen in various combinations, could reproduce every color in the visible spectrum. They were called additive because they literally added up to pure white light. Eight years later, French pianist Louis Ducos Do Hauron devised the idea of three subtractive primaries. These colors–cyan, magenta, and yellow— can also mix to produce any hue in the visible spectrum, but rather than adding light, these three do it by filtering it out!

@joekotlan on X