When I read a book I have the habit of highlighting certain passages I find interesting or useful. After I finish the book I’ll type up those passages and put them into a note on my phone. I’ll keep them to comb through every so often so that I remember what that certain book was about. That’s what these are. So if I ever end up lending you a book, these are the sections that I’ve highlighted in that book. Enjoy!

A Palette of Question Types:

Questions that gather context and collect details

- Ask about sequence – Describe a typical workday. What do you do when you first sit down at your station? What do you do next?

- Ask about quantity – How many files would you delete when that happens?

- Ask for specific examples – What was the last movie you streamed? Compare that question to What movies do you stream? The specific is easier to answer than the general and becomes a platform for follow-up questions.

- Ask about exceptions – Can you tell me about a time when a customer had a problem with an order?

- Ask for the complete list – What are all the different apps you have installed on your smartphone? This will require a series of follow-up questions–for example, what else? Very few people can generate an entire list of something without some prompting.

- Ask about relationships – How do you work with new vendors? This general question is especially approproate when you don’t even know enough to ask a specific question (such as in comparison to the earlies example about streaming movies). Better to start general than to be presumptive with a too-specific question.

- Ask about organization structure – Who do the people in that department report to?

Questions that probe what’s been unsaid

- Ask for clarification – When you refer to ‘that’ you are talking about the newest server right?

- Ask about code words/native language – Why do you call it the bat cave?

- Ask about emotional cues – Why do you laugh when you mention Best Buy?

- Ask why – I’ve tried to get my boss to adopt this format, but she just won’t do it… Why do you think she hasn’t?

- Probe delicately – You mentioned a difficult situation that changed your usage. Can you tell me what that situation was?

- Probe without presuming – Some people have very nagative feelings about the current government, while others don’t. What is your take? Rather than the direct What do you think about our government? or Do you like what the governement is doing lately? This indirect approach offers options associated with the generic “some people” rather than the interviewer or the interviewee.

- Explain to an outsider – Let’s say that I’ve just arrived here from another decade, how would you explain to me the difference between smartphones and tablets?

- Teach another – If you had to ask your daughter to operate your system, how would you explain it to her?

Questions that create contrasts in order to uncover frameworks and mental models

- Compare processes – What’s the difference between sending your response by fax, mail, or email?

- Compare to others – Do the other coaches also do it that way?

- Compare across time – How have your family photo acitivies changed in the past five years? How do you think they will be different five years from now? The second question is not intended to capture an accurate prediction. Rather, the second question serves to break free from what exists now and envision possibilities that mey emerge down the road. Identify an appropriately large time horizon (A year? Five years? Ten years?) that helps people to think beyond incremental change.

Overall, the objective of interviewing is to learn something profoundly new. The following are the key steps in the interviewing process:

- Deeply studying people, ideally in context

- Exploring not only their behaviors but also the meaning behind those behaviors

- Making sense of the data using inference, interpretation, analysis, and synthesis

- Using those insights to point toward a design, service, product, or other solution

What you observe as a need may actually be something that your customer is perfectly tolerant of.

Interviewing customers is tremendous for driving reframes, which are crucial shifts in perspective that flip an initial problem on its head.

Here are some situations where interviewing can be valuable:

- As a way to identify new opportunities

- To refine design hypotheses, when you have some ideas about what will be designed

Reframing the problem extends it; it doesn’t replace the original question.

User Research Approaches

- Usability Testing – Users interact with a product and various factors (time to complete a task, error rate, preference for alternate solutions) are measured.

- A/B Testing – Comparing the effectiveness of two different versions fo the same design

- Quantitative Survey – A questionnaire, primarily using colsed-ended questions, distributed to a larger smaple in order to obtain statistically significant results

- Focus Group – A moderated discussion with 4 to 12 participants in a research facility, often used to explore preferences (and reasons for those preferences) among different solutions

- Central Location Test – In a market research facility, groups of 15 to 50 people watch a demo and complete a survey to measure their grasp of the concept, the appeal of various features, the desirability of the product, and so on.

Interviewing isn’t the right approach for every problem. Because it favors depth over sample size, it’s not a source for statistically significant data. Each interview will be unique.

Interviews are not good at predicting future behavior or uncovering price expectations.

Empathy in this situation might even be as simple as seeing “the user” or “the customer” as a real live person in all their glorious complexity.

You should have a hunger to learn from the participant that should be broad, not specific. Be curious, but not yet sure what you are curious about.

Transitional rituals are actions we take to remind ourselves that we are shifting from one mode ofbeing to another. An example of a transitional ritual is to make a small declaration to yourself and your fellow fieldworkers in the moments before you begin an interview. If you are outside someone’s apartment or entering their workspace, turn to each other and state what you are there to accomplish.

Try to not bring your world into theirs. Leave the company-logo clothing (and accessories) at home.

Be ready to ask questions for which you think you know the answer. The goal here is to make it clear to the participant (and to yourself) that they are the expert and you are the novice.

Eliminate Distractions

Tactically, make sure that your are not distracted when you arrive. Take care of your food, drink, and restroom needs in advance.

If your brain is chattering, “I’m so hungry” you are at a disadvantage when it comes to tuning into what’s going on in the interview.

Silence your phone and don’t plan on taking calls or checking texts or emails during the interview.

Your participants have no framework for “ethnographic interviews” so they will likely be mapping this experience onto something more familiar like “having company” (when being interviewed at home) or “giving a demo” (when being interviewed about their work).

Don’t dwell on the chitchat, because your participant may find this confusing.

Think about when to reveal something about yourself (and when not to). Putting a “me too!” out there change the dynamic of the interview.

You should definitely talk about yourself if doing so gives the other person permission to share something.

Don’t try to solve the problem of the complex dynamic you just walked into; Just focus on the next problem – the immediate challenge of what to say next.

Consider speaking directly to the person you are visiting before the day of the interview, in order to get that person-to-person comunication started early.

There’s often a visceral point in the interview where the exchange shifts from a back-and-forth of question-and-answer, question-and-answer to a question-story setup. Stories are where the richest insights lie, and your objective is to get to this point in every interview.

Frame some of your questions with phrases such as “What I want to learn today is…” as an explicit reminder that you have different roles in this shared, unnatural experience.

If you are following up on something other than what the participant just said, indicate where your question comes from. For example, “Earlier, you told us that…” or “I want to go back to something else you said…” Not only does this help the person know that you’re looping back, it also indicates that you are really paying attention to what they are telling you, that you remember it, and that you are interested. If you are going to change topics, just signal your transitions: “Great. Now I’d like to move on to a totally different topic”

Consider the example described by Malcolm Gladwell in his article The Naked Face. He describes the work of psychologists who developed a coding system for facial expressions. As they identified the muscle groups and what different combinations signified, they realized that in moving those muscles, they were inducing the actual feelings. He writes: Emotion doesn’t just go from the inside out. It goes from the outisde in…In the facial-feedback system, an expression you do not even know that you have can create an emotion you did not choose to feel.

Before you head out to the field, get the team together and do a cleansing brain dump of all the things you might possibly expect to see and hear, leaving you open to what is really waiting for you out there.

We were not able to change the underlying cultural issues that wer causing this issue (nor were we trying to), but we were able to use our expertise in planning and executing these sorts of studies to help resolve the deadlock.

If it’s very challenging to find the people that you expect (or are expected) to do research with, that’s data.

Additional Resources

For more on recruiting, check out Chapter 3 of Bolt/Tulathimutte’s book called Remote Research

For more on the power of suprises throughout the research process, check out “What to Expect When You’re Note Expecting It” by Steve Portigal & Julie Norvaisas, interactions March + April 2011 at http://rfld.me/QYGII8

A complete example of a field guide template can be found at http://rfld.me/QBeotb

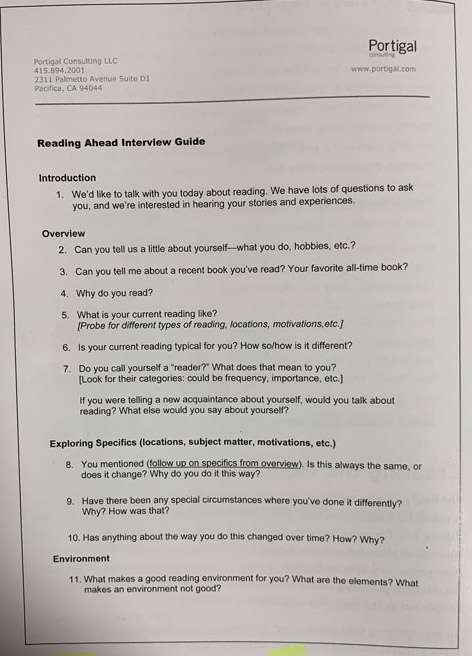

Be sure to assign durations to the different sections and subsections. Again, you aren’t necessarily going to stick to the exact duration in the actual interview, but it helps you see if you’ve got enough time to cover everything you are expecting to cover. Write most questions as you would ask them (“IS there a single word that captures the thing you most like about wine?”), rather than as abstracted topics (“A single word that represents what they like about wine”).

There are no wrong answers; this is information that helps us direct our work.

Near the end of the interview is a great opportunity to ask more audacious questions. They’ve become engaged with you. You’ve earned their permission. Examples are:

- If we came back in 5 years to have this conversation again, what would be different?

- If you could build your ideal experience, what would it be like?

A typical interview concludes with some basic questions and instructions:

- DId we miss anything? Is there anything you want to tell us?

- Is there anything you wan to ask us?

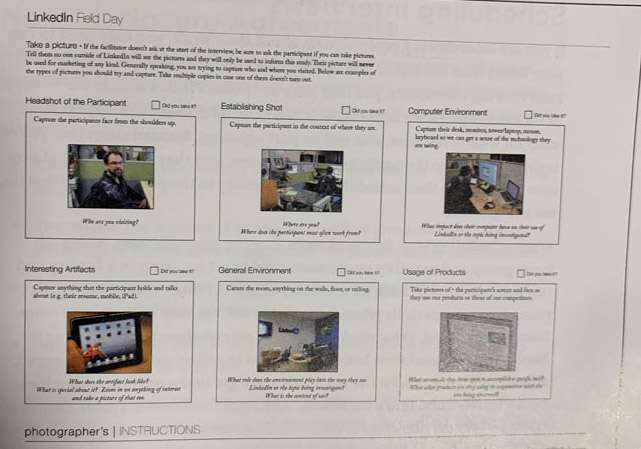

A great addition to a field guide is to create a list of photos that you hope to capture while out in the field.

“What is your process for updating playlists?” With that question, the participant is being asked to verbally summarize a (potentially detailed) behavior, from memory. But, it’s not going to be accurate information. By asking “What is your process for updating your playlists?” we are actually learning the answers to the (unaksed) “How do you feel about the process for updating playlists?” and “What are the key steps you can recall in the process for updating playlists?” Now, a slightly different expression of the question is “Can you show me how you update your playlists?” Now you’ve staged an activity.

You might try a slight variation, shifting to a participant-observation dialogue, such as, “Can you show me how I should prepare coffee?”. Your question directs her to explain specifically each step so that you can perform it. Asking that person to play the teacher role not only reinforces the idea that she is the expert here, but it also can make it easier for her to articulte the details you are seeking.

In addition to seeing the operation of the coffee machine, I saw a great dela of context – what other devices were be used, who else wa around, what happened before, and what happened after.

Shifting the discussion from the conceptual to the tangible (even when being tangible means being fantastical) is one way to get at hard-to-uncover information.

Participants may decide their ideal product needs a handle. But we know that really means that they need an easy way to move it from place to place, and we know that there are dozens of ways to satisfy that need.

Concept Testing – show concepts that are not viable or otherwise unlikely in order to explore the edges of factors that influence desirability, usefulness, and so on. What you’re learning is not an evaluation of the concept, but instead a deeper understanding of the design criteria for a future solution.

You aren’t asking questions about their needs (say, their expectations for a device’s size), but rather you are asking questions about a concept in order to elicit, among other feedback, their expectations for the device’s size.

There’s a difference between what you want to know and what you ask.

Go to the interview with a set of specific topics you’re looking for feedback about, but it’s important to let the participants structure most of the response themselves. Put the concept in front of them, with whatever explanation or demonstration you’ve planned, and then ask them an open-ended question such as “What do you think?” The topics they choose themsleves are the strongest natural reactions. The concerns and delights they express are critical.

If you bring out a concept by saying “Here’s something I’ve been working on…” you’re activating a ntural social instinct that will diminish their comfort in being critical. “Here’s a whole bunch or early ideas that I was asked to show you” or “I’ll be curious to hear what you think of this one” are better.

If participants percieve you as having ownership over the concept, they may turn the interview back on you: “Will this be backwards-compatible?” “How much will it cost?” Do not answer those questions. Do the Interviewer Sidestep and turn the question back to them: “Is that important to you?” “What would you expect it to be?”

Although you may not see that path the lead interviewer is on, as the second interviewer, it’s important not to interject in a way that can interrupt the flow.

It’s the job of the lead interviewer to move the interview from one chapter to the next. The lead interviewer will create opportunities – usually at the ends of these chapters – for you to ask questions.

If they refer to a product, brand, or feature inaccurately, don’t correct them explicitly or implicitly.

Use open-ended questions: Less Good – “What are three things you liked about using the bus?” Good – “Can you tell me about your experience using the bus?”

You can provide the interviewing assistant with sticky notes to write his questions on as he thinks of them (so even if the asking is deferred, at least capturing the question provides some-albeit muted-immediate gratification).

You can set aside time for the interviewing assistant to ask questions within each topic area before you move along, asking him “Is there anything that we’ve talked about so far that you;d like to know more about?” I tell my fieldwork attendees that we can have a brief conversation in front of the participant about any questions the have; they may want to suggest a topic to me rather then constructing the question directly themselves, which enables me to pick that question up or defer it as I choose. (For example, “Steve, I’d love to learn about how Jacob send the documents to accounting.”)

Kick-Off Question – “Maybe introduce yourself and tell us about what your job is here?” It doesn’t matter too much what it is, as you are going to follow up with many more specific questions. The key here is not to start too specifically (“Ahem. Question 1. What are the top features in your mobile device?”)

There’s no formula for how long it takes people to get past discomfort. This discomfort presents itself in subtle ways. You may observe stiff posture and clipped deliberate responses. They may fend off your questions by implying that those are not normal things to be asked about, or providing little or no detail about themselves, describing their behavior as “you know, just regular”. You may have to identify your own feelings of discomfort. You have to accept this as awkward.

Give your particpant plently of ways to succeed. Ask her easy questions. This isn’t the time to ask challenging questions or to bring out props

If you’re following your field guide linearly, you may get a good portion of the way though in a short time and begin to feel some panuc about the amount of questions you’ve come with. Just stick with it; the remaining questions will take longer to get through (and will generate more follow-up questions, too).

There’s often a point when the participant shifts from giving short answers to telling stories.

Just because people are speaking about a future (say, how mobile phone will change their relationships) doens’t mean it’s an accurate prediction. These parts of the interview often produce phrases or ideas that the field team will continue to repeat and go back to as they distill complex issues into visionary notions.

The Doorknob Phenomenon – Where crucial information is revealed just as the patient is about to depart. SO consider keeping your recording device on, even if it’s packed up. You may see something in the environment to ask about. Keep your eyes and brain in interview mode until you are fully departed. Even if you are tired and ready to leave, stifle the inner “Oh, there’s nothing here” voice that wants you to pull the plug. Stick with it a couple of minutes more. Those may be the bits of recorded data that pull the whole project together for you in the analysis phase.

Go ahead and refer to the field guide as you need to, but don;t let it run the interview. Despite your planning, the interview probably won’t unfold the way you anticipated. If it does, perhaps you aren’t leveraging the opportunities that arise.

If you’re at the very beginning of a stufy, you should rely more on the guide than you will once you’ve learned form a couple of interviews.

“What did you have for breakfast yesterday… was it toast or juice?” The novice interviewer is suggesting possibly responses, and his interviewee is just that much more likely to work within the interviewer’s suggestions rather than offer up her own answers.

Ask your question and let it stand. Be deliberate about this. To deal with your (potentially agonizing!) discomfort during the silence, gice yourself something to do–slowly repeat “allow silence” as many times as it takes. If the person can’t answer the question, she will let you know.

After she has given you an answer, continue to be silent. People speak in paragraphs, and they want your permission to go on to the next paragraph.

“I’m thinking” cues include hand rubs chin, eyes gaze away, lips pursed.

As a rule, if your question isn’t fairly obviously a follow-up question, you should preface it with some transitional words.

You won’t get the answer to your questions just by asking – for most threads in interviews, you need to use a series of questions to get to the information you want. It’s not that people are being difficult; they just don’t know what it is that you want to know.

When you listen to your participant answering your question, be vigilant. Do they appear to have understood what you intended by the question, or have they gone somewhere else with it?

Jot quick notes on your field guide about what you want to come back to, so you don’t forget.

“At no point had Kieth told us that he had old and new versions of himself Keith was always just Keith” – just because a framework isn’t rejected by the participant doesn’t mean it is accurate.

Find out for sure, from the subject’s perspective, rather than leaving things to your own inference.

‘His decent into lecture mode was complete; he was not asking questions, but instead was sharing his own beliefs. He had transformed for a listener to a teller.”

You are conducting the interview to learn from this person, so there’s no need to assert your own expertise. In fact, once you do so, you can lose control over the interview entirely, as the participant will simply turn it around and ask you, “Is there a way to do ______?” “How can I make ______ happen?”

Your field guide is a guide. Set it aside until you really need it. Leading the interview successfully comes down to you.

Although it’s tricky, ask the shortes question you can, without directing them to possible answers you are looking for. Then be silent.

Reflect back the language and terminology the your participant used (even if you think it was “wrong”).

When taking notes, you should be descriptive, not interpretive. If Larry tells you he has worked 14 hours a dat for the last 10 years, your notes should read “Worked 14hrs/day for 10 years,” not “Larry is a workaholic”.

If you can’t get an image of the participant’s online banking screen, you can sketch the different regions of the interface and write callouts for some of his comments. Because he can see the sketch, he can be reassured that you aren’t capturing private information and can clarify and correct your notes.

After you leave the fieldwork site, go for food and drink and talk about the interview. The longer you wait, the less you will remember.

Take lots of pictures; they often reveal something different later on.

Sometimes you might find yourself in a different situation than you had anticipated. For example, an interview with a certain type of professional turns out to be an interview with that person and his manager. If you can’t get the interview you want, be aware of the dynamics and adjust your questions appropriately.

When the participant won’t stop talking give them space to tell the story they’ve chosen to tell you and then redirect them back to your question.

Consumers might default to treating your interview like a visit. Professsionals often frame the interview as a meeting.

People influence each other simply by being together. The more people you include, the more you’ll experience that effect.

The first part of the interview should be understanding the participant’s workflow, objectives, pain points, and so on. Then, when you share the artifacts you’ve brought, you have a better chance at understanding why they are responding the way they do.

A Word document is more formalized then an email but less formal than a Powerpoint presentation. Ongoing dialogue is usually in email; the final presentation is in PowerPoint.

@joekotlan on X